Housing Choice

- Ryan Kilpatrick

- Jan 31, 2019

- 10 min read

Over the last year I have spent countless hours talking with local, regional and statewide organizations about the importance of housing choice in the market place. In addition to municipal officials, community foundations and developers, I've also been talking with chambers of commerce, Elks and Rotary Clubs and corporate board members.

Without fail, every group I talk with includes some very engaged citizens who are surprised to hear about the subtle but impactful ways that local zoning policies have undermined housing choice. As one of the basic principles of market economics, we understand that a limited set of choices can often lead to higher prices over time. Rarely do we take the time to think about how this applies to housing.

As a quick example, when we buy typical consumer goods - say tissues- in the market place, our ability to purchase those items are rarely limited by local governmental impositions. Most of the time, we have the choice to purchase a single box at the grocery store, a bulk package of tissues at Costco, or a compact package that fits in a glove box or purse. Depending on how much of the product we expect to use and how we need it to fit in to our daily routine, we have a number of choices. Each choice comes with both benefits and trade-offs.

$0.99 for 30 $17.99 for 1,500

Basic principles of economies of scale come in to play here and can have significant benefits for those people who prefer to buy in bulk and have a need to use all 1,500 tissues in the bulk package.

Although you will spend 2.7 times less per tissue when you purchase the bulk package, you are also spending 18 times more on the front end of that purchase than you would otherwise pay for the mini-pack. If all you really needed was to have a handful of tissues for your glove box, the bulk package is a bit ridiculous. It would be silly to require you to purchase the bulk package. Yet, this is exactly what we often do with housing.

In this blog post, I will cover the importance of housing choice in a free market system and what we mean by this term. In upcoming posts I will explore why housing choice has been undermined, how it impacts housing at all price points, and what we can do to fix the regulatory system.

What do we mean by housing choice?

In most communities around the U.S., and especially in West Michigan, there are just a handful of housing types that are readily available in the market.

The single family, detached house is the most ubiquitous form of housing and the primary symbol of the American Dream - or at least the version of the American Dream that was often referred to in the post-war era from 1950 to about 2000. This housing type is permitted across a majority of the land area in almost every community in West Michigan- but there's a catch we'll explore in more detail. Don't forget about that tissue example above.

The garden style apartment is another common housing type in West Michigan. Most communities plan and zone for this type of housing along the edges of the community or near auto-oriented commercial corridors where single family housing is less likely to be in demand.

Finally, mobile/manufactured homes are an additional housing type that is relatively common across the State. These types of homes are currently the most viable opportunity to provide a significant number of units at relatively affordable prices and without needing to rely on state or federal subsidies to fund them. Due to state legislation (PA 96, 1987) which prohibits local communities from excluding them entirely, mobile/manufactured home communities are a relatively common type of low cost housing in Michigan, but there is quite a bit of room to improve on the existing model. Interestingly, this segment of the housing market may be undergoing the most rapid and innovative changes over the next 10 years. MH Village is a great resource for following some of these changes.

The above three options are a quick (and very generalized) distillation of the types of housing that are most often permitted and constructed in West Michigan, and especially since the 1980s. These options do provide some choice to local households, but the trade-offs associated with each choice can be significant in many cases. Access to quality schools, employment, daily necessities, health care, etc. can all be impacted by where these housing choices are available. As a result, these factors play a big role in determining how competitive each choice actually is in the market place.

What are we missing?

The modern limits (and potential) of single-family

The concept of a single family home has changed quite a bit since 1950. In those early post-war years, the average size of a new home was about 900 square feet. Several versions of the Levittown homes started at 750 square feet and offered excellent opportunities to build equity for young families and first-time buyers.

Yet, by 2017, the average new home was almost three times as large. This is despite the fact that real wage growth has been relatively stagnant for middle class earners since the late 1970s. If you haven't yet read Dave Ramsey's work on the subject of home size and debt, here's a quick primer on how housing size can impact a family's pocket book.

As Ramsey points out, when households and families make housing choices that allow them to live within their means, they tend to be much better off in the long run. The problem is, we are building fewer and fewer options for families to choose from that are within their price range.

Remember the example of the mini-pack of tissues vs the bulk package from Costco at the top of this post? The same principles apply to housing. A home buyer can spend less per square foot if they choose to buy a 2,500 square foot home as compared to a 900 square foot home with the same level of finish. If buying the largest house possible is your goal, then the savings per square foot are important. However, the total sticker price for the 2,500 square foot home is much higher than the total price of a 900 square foot home. If you care less about the size of your home and care more about your monthly out-of-pocket costs, the smaller option is a critical choice to have in the market.

So, why aren't more builders and developers offering 900 square foot options?

The answer is two-fold. First, most local communities have established minimum lot sizes and minimum square foot requirements for new housing construction. Sometimes these minimums are reasonable, and sometimes... not so much.

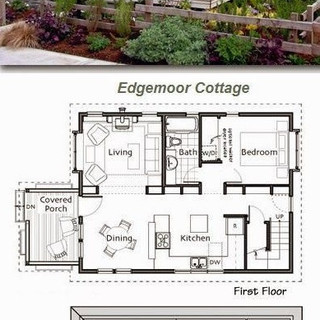

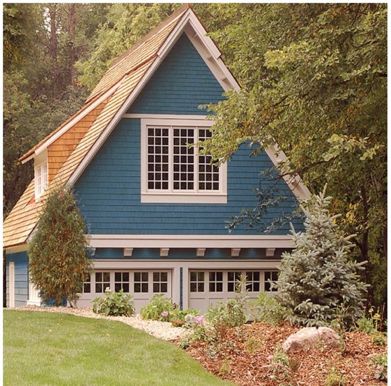

The images above illustrate a series of 700 to 1200 square foot homes that would not be permitted in many cities and townships in West Michigan because they are too small. Very often, local units of government have requirements that set the minimum square foot size of a newly constructed house at 1,200 ft or more. In addition, most communities require large lots of 8,000, 10,000 or 15,000 square feet for even their higher density residential districts. These lot sizes are often double the average platted lots created prior to the 1970s.

The 1,080 square foot cottage homes above might just barely meet the minimum size requirements in some communities, but the yard areas are too small to satisfy most local ordinances. Because the units are smaller, the profit margins for a developer are also smaller and there is less incentive to pursue this market. However, where units are permitted to be clustered, as pictured below, the infrastructure costs to serve the site are reduced and the economics begin to make sense again.

Unfortunately, when municipalities require 80-100 feet of road frontage and 10,000 square feet of yard area per dwelling unit (or more), the developer must pay to install infrastructure across all of those large lots. The only way to pay for that infrastructure cost is to build larger homes that sell for high enough prices to absorb the costs of all that extra sewer, water, gas, electric, cable and road infrastructure being strung across those wide lots.

Financial merry-go-round

Local municipalities are not the only parties influencing what gets built and how big it is. For the most part, new housing construction is financed using a combination of developer/investor equity and debt from major lending institutions. Most banks will require that a developer 'prove' a market exists for the type of product he/she would like to build. In order to prove the market, the developer must find comparable sales within the market which have recently sold for an amount close to the proposed selling price of the new homes the developer would like to build. The problem with this model is that most single family homes built since 1990 are 1,500 square feet or larger and the model for building those homes is centered around what we described above - large lots, expensive infrastructure and big homes to justify the cost of land and utilities. This means that when a developer looks for comparable sales to support the new construction of a 900 to 1,000 square foot home, the only comparable sales are likely to be 50+ year old homes in need of extensive repairs. Proving the market means that a local investor must be willing to invest the majority of the cost necessary to build a project without the backing of a large lender. In a later post we will unpack what these costs might look like and how we could assemble a project to prove the market.

What's Old is New Again - Multi-unit Housing Types

The types of housing that are increasingly difficult to come by - the choices that largely do not exist in local markets - are the same types of housing for which there has been a significant increase in demand over the last decade. For the most part, there has been a dramatic increase in demand for higher density housing within close proximity to local or regional amenities. Very often this is housing within or close to a traditional downtown or Main Street environment, but it also includes developments in which the housing is clustered in a relatively small portion of the site in order to preserve a much larger land area for natural space, recreation or agricultural production. These housing types come in four basic varieties:

1. Large-format, multi-unit, urban development. These projects tend to have much smaller units than traditional garden style apartments but with a higher level of design, finish materials and on-site amenities. These developments are designed to allow residents to spend a significant amount of their time (and expendable income) in the neighborhood rather than only within their homes. These projects work best in close proximity to small businesses, coffee shops, restaurants and employment centers where parking can be shared and residents can choose to walk, bike or drive to their local destinations.

Over the last 15 years, most regional real estate markets with a growing population have demonstrated there is significant demand for this type of housing. In many markets, high demand is coupled with a very limited supply of available product which has produced the oft-discussed effects of gentrification and displacement among populations who are unable to afford the rising rents that come with increased demand. In a later post, we'll explore strategies to reduce or eliminate displacement while continuing to foster urban growth in strategic neighborhoods.

The large format, multi-unit buildings are best placed along commercial corridors or in the midst of a downtown area where there is adequate infrastructure to support walkable neighborhoods and a variety of mobility options. These types of projects tend to cost anywhere from $5 million to $50 million, depending on their size and design. They are therefore most often undertaken by wealthy investors and where market demand is significant.

2. Smaller format, multi-unit buildings. This is often referred to as Missing Middle housing and includes two-family, three-family, four-family and small apartment buildings (5 to 15 units). These building types are best located within a 5-10 minute walk of a commercial center or local business district and tend to require only one parking space per unit.

This building type typically does not need a yard area but does benefit from an 8-10 foot setback from adjacent homes and buildings to ensure adequate light on all sides of the building.

Small format multi-unit buildings are best located as transitional building types between larger format buildings and traditional single-family buildings. This housing type is also often found on higher traffic corridors within neighborhoods. These project types tend to cost between $500k and $5 million and are much more manageable for mom and pop type investors, non-profits and younger entrepreneurs.

3. Townhomes. This building type was once ubiquitous on the fringes of a downtown or Main Street environment and is characterized by an attached party wall separating one housing unit from the next. Each unit tends to occupy all of the vertical space on a small patch of ground, but can often include a front porch as well as a small back yard.

An attached or detached garage for each unit is often in demand when town homes are constructed as a for-sale product. However, in order to maximize land values, townhomes are often constructed on lots as narrow as 15-16 feet and only accommodate one enclosed parking space in the garage.

4. Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs). These are secondary housing units that can be tucked inside of a single family home (basement or attic apartment), above the garage, or built as a stand alone backyard cottage. This concept was typical in historic neighborhoods and used to be referred to as the carriage house. Later, granny flat or mother-in-law apartment became popular terms.

Historically, it was very common for home-owners to partition sections of their home and rent out a room or an entire small apartment. This was especially common during times of economic downturns and served as an excellent means to offset expenses with an existing asset.

These four housing types are critical options that have the potential to reduce costs for all buyers and renters in the market over time. However, the basic rules of supply and demand will still apply. For as long as demand exceeds supply, rents will continue to go up. See our previous post about the housing needs in the region for more data about housing demand in the region.

It's important to keep in mind that all new construction is expensive. Without some form of subsidy, we will not achieve immediate affordability for low income renters with newly constructed units. However, for as long as the above housing types are either outlawed entirely or extremely difficult to build due to local zoning requirements, there are severe limitations on the amount and type of supply that can be built. This will continue to put upward pressure on prices.

We will have to pursue strategies that leverage a multitude of financial resources in order to make sure that housing is available at all price points. However, the lowest hanging fruit is our ability to leverage the private market and allow investors and developers to build the kinds of housing products that are in demand and financially viable without subsidies. This starts with allowing a much greater diversity of housing choices in the market.

Individuals frequently wonder 'Why is solar based energy great?' and, thus, neglect to understand the significance of solar powered innovation http://sunmaxsolar.jigsy.com/. Solar based power has clearly turned into the pattern in environmentally friendly power. Property holders around the UK introduced solar powered chargers on their rooftop, overseeing likewise to harvest all the solar oriented energy benefits.

Facebook is without a doubt the most well known web-based entertainment stage accessible with many benefits related with it. It is basically an interpersonal interaction site facebook smm panel, but it very well may be utilized as a convenient device for advancing and publicizing a business. We can utilize Facebook to advance a brand, market an organization, or make mindfulness about a help or an item.

Before you start utilizing your Fire television Stick, you'll need to coordinate the remote. The interaction can differ contingent upon which model you have pair firestick remote, and only one out of every odd remote is exchangeable with every age of Amazon Fire television. This is the way to coordinate or reset your Fire television Stick remote.